feature-ContactCover_1

Our profession – policing – has had some hard-earned lessons. Lessons that were caused by the deaths of or serious injuries to officers. Some of those lessons might be considered “old,” but their validity should not be based on their age. They are just as important and viable today as they were when they were first pushed out to in-service and recruit classes. That’s true even if they appear to have been forgotten by the last generation or two of field training officers and sergeants.

Why?

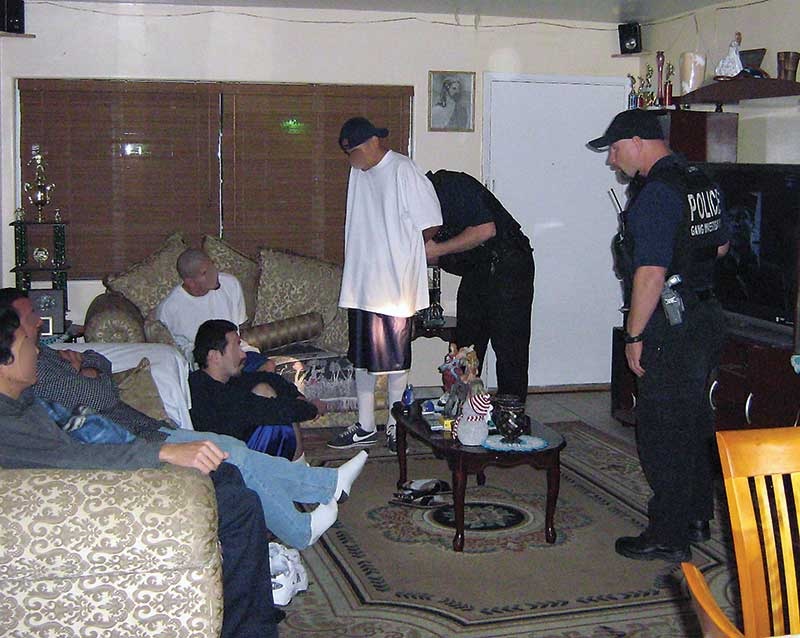

The cover officer’s view – watching the subject and the area while the contact officer handles their role.

Recently, I read about an officer-involved shooting in the South. The media reported an officer was searching a car and found narcotics inside the car. Once that discovery was made, the suspect got into the car and drove off – with the officer inside. When the suspect did not stop, the officer used deadly force against the suspect to stop his flight with the cop inside the car. The shooting resulted in a crash that injured both the suspect and the officer. No mention was made of an officer chasing the fleeing vehicle.

Thinking about this and realizing I do not have the incident report, I could not help but wonder where was the Cover officer? Who was watching the BadGuy during the search? Who could have prevented the BadGuy from getting back in the car?

While I understand the decrease in officers and call volumes, there are some things we should not do without cover officers. If the reporting was correct, searching a suspect vehicle in the presence of an unsecured suspect is one of them.

What?

Aside from restrained detention, we can utilize the Contact and Cover principle.

What is it, you ask? Where did it come from? You should have learned this in your academy and from your FTO.

As mentioned, our hard-earned lessons and changes in our practices generally come from tragedies. That happened to two San Diego, CA police officers – Kim Tonahill and Tim Ruopp – who were murdered On September 14th, 1984.

The subsequent murder investigation determined that while one officer searched a suspect, the other was completing a citation. That suspect assaulted the first officer with a handgun before shooting the second officer. In other words, it seemed that neither of the officers was watching the event ready to identify and respond to any threats to their partner – regardless of what subject caused it.

How?

The concept is that one officer handles all of the contacts (obtaining ID, Terry frisk, field interviews, and the like) for all subjects or suspects. In contrast, the other officer covers the first. They stay out of direct interactions with those subjects unless they must intercede to prevent or stop an attack.

While the method might not be new, it was only codified in the aftermath of those now forty-year-old murders and a third one from the following year. Several San Diego PD officers were involved in defining the technique and pushing it out in training. They included Steve Albrecht, John Morrison, Chuck Peck, and others.

Any time you end up with more than one deputy or officer on a scene, they have distinct roles. As mentioned, the primary (or Contact) officer handles all of the interactions as well as the work – whether it is running those subjects to confirm their identity and locate warrants or searching the suspect vehicle. Meanwhile, the back-up (or Cover) officer does just that. They are the eyes and ears as it relates to the subjects being encountered. They are there as both a deterrence and the primary force option.

Additionally, the Cover officer needs to maintain awareness of the surrounding area. They are encouraged to share any intelligence on the subjects and the location if they have it.

Anything Else?

Yes, one officer can still make handle an encounter and make an arrest. But even with editor emeritus Roy Huntington, two cops would be safer.

There is another benefit: by having an officer who is not directly interacting with the subjects, the roles can be switched in the event of one of those occasional interpersonal conflicts stemming from prior encounters. And, if emotion becomes an issue, we all have the benefit of someone who can intercede and mitigate the issue.

Officers can and, if necessary, should switch roles when concerns like that are identified.

This does not mean only two officers are needed at a given location or on call. On the contrary, multiple officers may be needed. Several subjects in a car? While that may or may not require another Contact officer, it means another Cover officer will be needed when people are removed from the car and begin to be interviewed. One Cover officer pays attention to those in the car; another covers the Contact officer during their interactions.

Yes, this works great for car partners. It also works for beat partners. And quite frankly, it should be used by any set of cops who end up on a call or scene together.

I know that good partners want to jump in and help. However, helping with the safety of those cops on the scene is just as important as running the third person’s name and birthday. In fact, it is more important.

Final Thought

Several sources of information exist about Contact & Cover, its development, and how you, your partners, and your agency can employ it. We have covered it previously. As assaults of all kinds increase on uniformed officers, it makes sense to use the practical tools we have available to us for our benefit.

Resources:

Steve Albrecht’s books – Tactical Perfection for Street Cops and Surviving Street Patrol