AC-091021-DF-3-800

If you have been shooting for more than a day, chances are you already know, dry firing can improve one’s marksmanship and weapons manipulation. So just how much dry firing does it take? To effect change, such as learn a new method or technique? Maintain learned skills? Many will say, it takes around one thousand repetitions to engrain something new, into “muscle memory” as its generally called.

One thousand repetitions! That’s an intimidating number. But really, it’s not just the number of repetitions (although you do have to put in some reps), but how one conducts dry firing that makes a difference. When done correctly, one can learn a new task, smooth out and speed up movements to ultimate efficiency. All well under the thousand reps, many think is required.

WHY DRY FIRE?

But why dry fire? Especially if one regularly conducts live fire training. The answer can be found by looking at various other sports that demand intricate physical movements to be successful, such as boxers, MMA fighters even professional dancers, etc. Any professional fighter will tell you shadow boxing plays a vital role in their training.

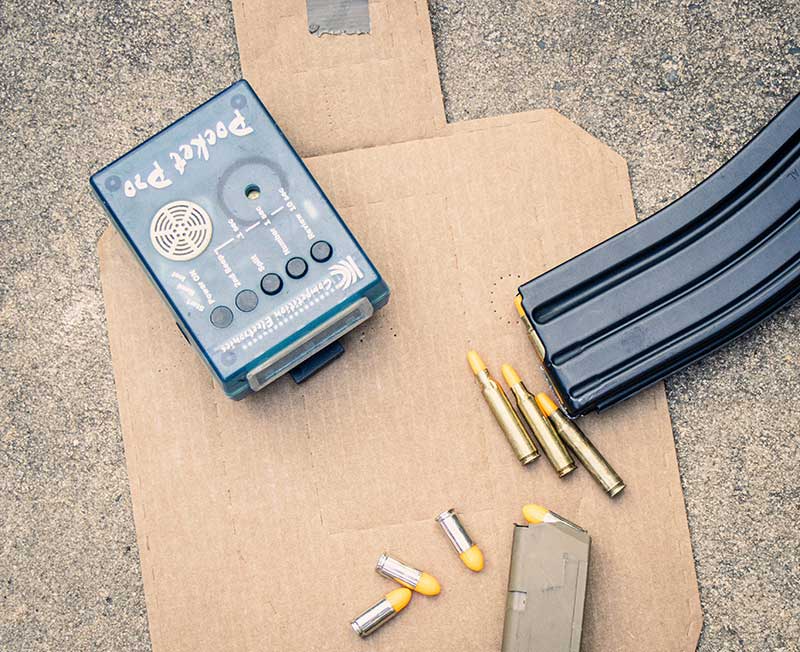

Practicing reloads, author prefers to dry fire in the back yard. Its easier on magazine landing on the grass instead of an indoor hard floor. Note brightly colored dummy rounds, help ensures no live rounds in play.

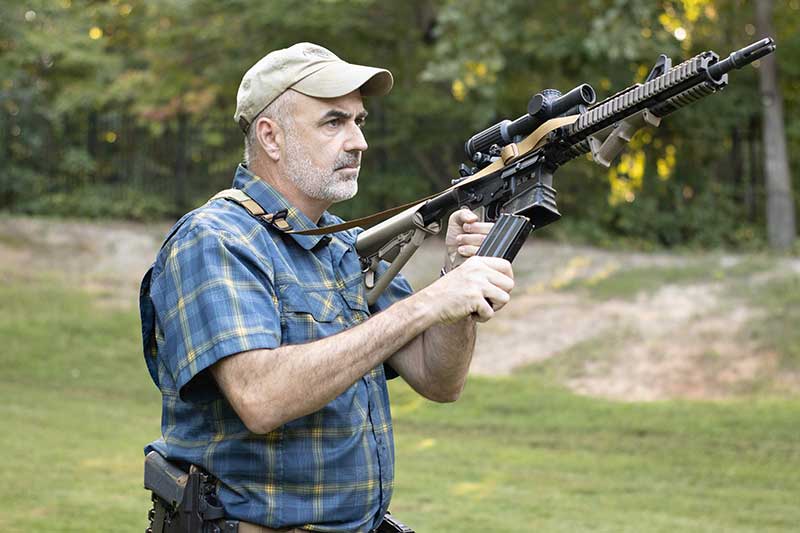

Ensure you have a target to practice aiming at. One more reason the author prefers dry firing outdoors and it allows setting up a target at a realistic distance.

Shadow boxing is the technique of practicing strikes, blocks, foot, and head movement, etc., going through the motions while striking nothing and allows fighter to focus on form, enabling them to streamline and optimize their strikes and movements. (Without the punishing effects of striking a heavy bag or taking hits from a sparring partner). Reinforcing their muscle memory (for lack of a better term) and enabling them to be able to strike and move at an instant, without deep thinking involved. Sound familiar? This is exactly the same thing you get from dry firing.

WHAT TO DO

Before you start just start busting out some reps you should first separate each task individually that makes up the action you want to work on. For example, want to enhance your pistol skills? Decrease your draw time, time it takes to reload etc. Don’t go right into a full sequence of drawing from the holster dry firing on a target then performing a reload with dummy rounds.

Instead, isolate one task and start there. First work on just on drawing and dry firing for several reps. After that, then just practice reloads from pistol aimed up on target with slide back on empty. (Slide-lock reloads).

After you have done both tasks separately and met your individual goal for each task (based on time, which I will get into further on), combine the two and go through the whole sequence together, drawing, dry firing, reloading, and dry firing again.

Breaking down the session into individual tasks first and practicing that way, allows one to put maximum focus on that specific manipulation. Instead of trying to master all the manipulations at once such as; drawing, firing, reloading etc.

Two items required to get the most out of your dry fire session: a shot timer to set goals and measure progress. Dummy rounds, to not only add an extra layer of safety but also reduce wear and tear on your firearm.

SLOW IS SMOOTH, SMOOTH IS FAST…TO A POINT

Dry firing should start out slow, meaning your movements are slow and deliberate. Doing so you are taking the time for your brain to tell your extremities exactly what to do. If you try to just burst into super-fast movements, you are not giving your brain enough time to process how to execute those fine movements, often resulting in, jerky unsteady movements, (the exact opposite of how to achieve speed). So, despite being totally overused and abused, the saying “Slow is smooth and smooth is fast”, does hold merit. Especially in regards to dry firing.

Deliberately and slowly at first, allows one to concentrate on the task and form. This is also a warmup before going into fast, explosive, and dynamic movement, which is the next step and goal in dry firing. Yes, slow is smooth and smooth is fast, but only to a point. After that slow is just slow. One needs to practice at full speed, as fast as one can. Practicing full speed is the next step and is just as important as starting out slow and deliberate.

TIMING IS EVERYTHING

So how does one know if they are doing it as fast as they can? To really get the most out of dry fire, one needs to be able to measure the time it takes to do something. Once you know that, you can then start chopping down the time allowed to do it, forcing you to do it faster. This is where working with a shot timer comes in. You can use an actual shot timer which allows one to set an audible start and stop time, or one of the many apps that are available for smart phones that will do the same thing.

The way to use a timer is as follows: Set a time interval that you can first pass doing the act at medium speed. For example, drawing from the holster and dry firing one shot. Give yourself say three seconds at first. One you can make that time three times in a row, then take a half a second off the clock to 2.5 seconds and repeat. As you decrease the allowable time you will of course have to speed up.

Dry firing not just for handguns. You can practicie an AR, bolt-lock reload, transition speed from AR to handgun, etc.

You want to so this until you cannot regularly make the time, once you hit this point this drill you will now at least know your capability. So, if you started at three seconds and you were able to get down to say 1.7 seconds, you now know your current capability and now have a goal for the next dry firing session.

Knowing what you can first achieve is important whether its dry or live firing. From there it’s all about continuing the streamlining process of getting rid of excess or wasted movement, allowing even faster results.

Just make sure when you start setting faster goals to only chop the time down by small increments. This allows you to work on one’s form and not be rushing to try and beat the clock. The goal is to smooth out movement to optimum efficiency. Not harsh, jagged, rushed actions, hoping muscle speed alone will get you there.

REPETITIONS HOW MANY?

Does it really take upwards of a thousand reps to learn and become proficient with a task? Not if dry fire is done correctly: starting out slow, isolating tasks, setting time standards then slowly cutting those times down. Using myself as an example. About four years ago I switched from running Beretta M9s and Smith & Wesson M&P 9mm pistols, to solely Glock 9mms. Going to Glocks I found I could not actuate the slide release the same way as I did with Smith & Wesson’s and Berettas.

I was always using my firing hand thumb to depress the slide release during rapid reloads. But doing so with Glocks, I had a habit of depressing it too early before that mag being fully seated. Of course, this led to a failure to chamber. The fix was to depress the slide release with support hand thumb after mag fully seated.

How much practice did it take to go to this other technique? About two months for me to get to the point that it is now natural and instinctive. Over that two-month period along with going to the range one a week for live fire. I dry fired on average, twice a week for perhaps 15 to 20 minutes at time. I did not keep track of dry fire reps but if I had to guess I did around 15 to 20 at most during those sessions.

So, if we do the math, let’s say 20 reps twice a week, for eight weeks. That comes out to 160 repetitions plus add in some reps during live fire. We are talking under 300 repetitions to learn and master the new chambering technique. That is well below the one thousand reps many say is required. I owe this to the methods I have covered here. I started out slowly focusing my concentration just on that one task. Then as I got proficient worked up to full speed.

The only way to improve is to first know what you can do, then try and beat that. Here two versions of Pocket Pro shot timers and a free shot timer app. They all allow one to set start and stop times that you can measure and test yourself with.

Then I timed myself and worked on performing that method of depressing the slide release during a rapid reloads, until I could make my previous time standard, I could do with my original method. Now this is not to say once I could pass my original time standard, I stopped practicing. While I don’t do it as often as when I was first learning it, when I do dry fire which is once or twice a month, I always ensure to practice some reloads to maintain my ability.

Lastly, two other helpful dry fire tips. First, always have a target to practice aiming at. Give your eyes a workout too, practicing focusing on the target sight picture and sight alignment. Second, use dummy rounds. Using dummy rounds as opposed to nothing, saves wear and tear on your firearm.

Specifically it prevents firing pin or striker over travel. (Which can damage the firing pin hole, flaring it out, leading to blown primers). Dummy rounds also ensure magazines retain their shape and keep feed lips from being damaged when being slammed into magazine wells during rapid reloads.

Whatever the goal is, decreasing draw times, performing lighting fast reloads, quicker transition from rifle to pistol. Dry firing should play a large part in your training regimen. Doing so, allows one to break down and focus on the specific manipulations required to complete a task.

Embed these movements into your brain, allowing them to become instinctive movements. Which in turn leads to speed and efficiency. After all, who doesn’t want to be speedy and efficient in a gun fight?

Jeff Gurwitch is Retired Special Forces with 26 years military service, nine tours of combat, and an avid competitive shooter.

COMPETITION ELECTRONICS

Pocket Pro, Pocket Pro II

www.competitionelectronics.com