feature-hr12

We know the law enforcement profession is stressful. And that the higher-risk encounters involve greater stress. Add to that the involvement of citizens in high-risk events where they are potential victims of or witnesses to, violent crimes. The totality of these stressors can be negative in both the near term and the long term as well, if not addressed. A question that follows is how best to train the Good Guys (and Gals) for these so that they can manage the stressors and prevail?

Given the stressors that can be present in these events, it is very likely that one’s heart rate will increase. Is that an increase from physical exertion? Or is it coming because of psychological input? Physiological? The answer? Yes. A combination of all three is likely, but that doesn’t mean we can train for it with just one tool.

The Curve

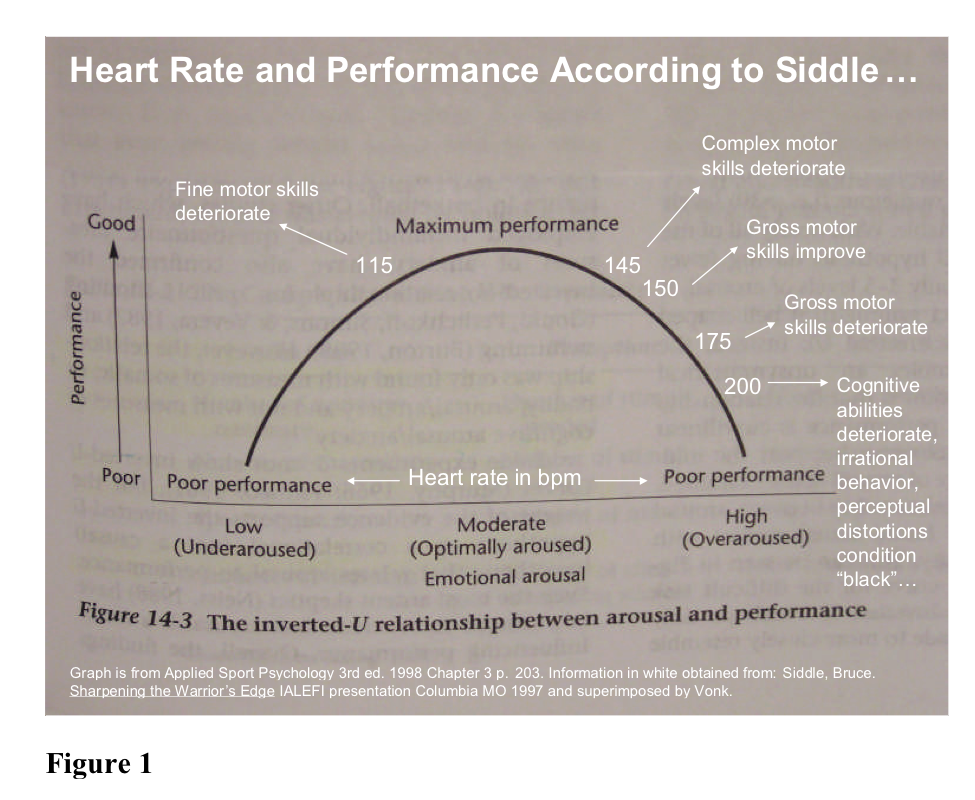

Yerkes-Dodson (circa 1908) determined that increased stress results in better performance – to a point. After that point, if the stressors continue to increase, one’s performance will suffer significantly.

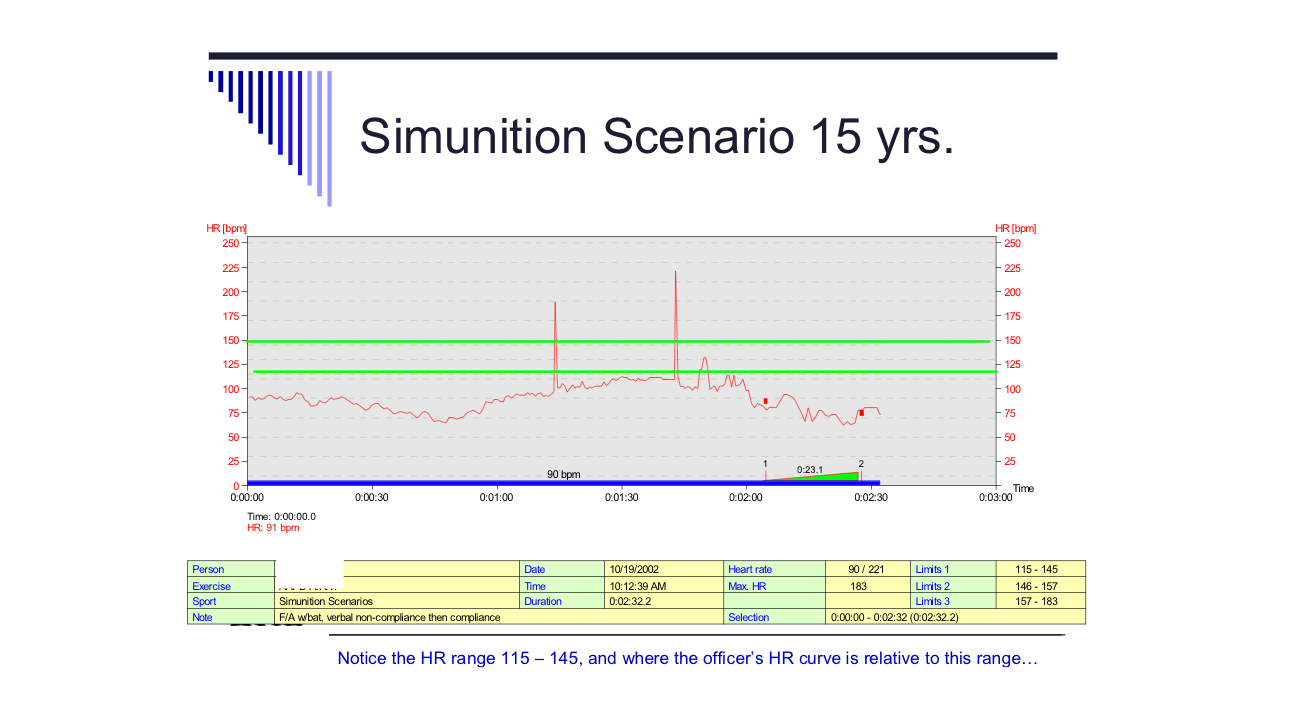

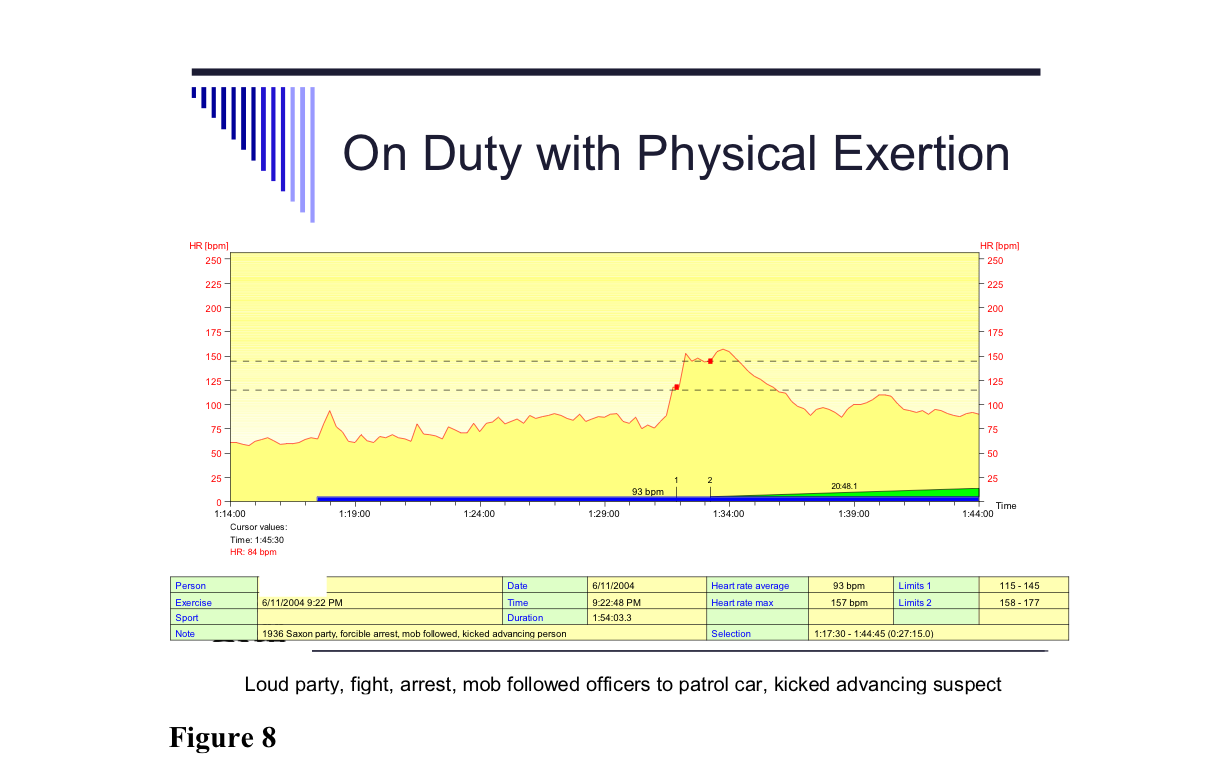

Some years ago, Bruce Siddle tied heart rates (HR) to performance. In short, he believed that someone’s maximum performance with their HR was between 115 and 145 beats per minute (BPM). Beyond that, an individual’s performance was degraded and would increasingly suffer based on the increased heart rate. At 145 BPM, fine motor skills would deteriorate; while gross motor skills could improve at 150 BPM, they will fall at 175 BPM.

This was demonstrated with the inverted U from Yerkes-Dodson. This led to discussions about shifting from fine to gross motor skills, as one would have greater difficulty performing those finer skills.

Many in the training community believed that one could simulate the psychological and physiological stressors present in these events through physical stressors. In other words, making students run, perform calisthenics, and the like would push them into an elevated HR that would replicate someone committing violence on them or another person.

In the 2006-2008 time frame, I read the first indications that Siddle was mistaken – even if I managed to err in that area a time or two going forward.

Vonk’s Efforts

During that time frame, I saw articles from Kathleen Vonk in various law enforcement magazines about her research into heart rate and its impact on performance during stressful events. Vonk was a working police officer in Michigan with a Bachelor of Science degree in exercise science. She taught at a police academy and for Heckler & Koch’s International Training Division. Vonk was the National Tactical Officers Association chairperson for physical fitness.

One article by Vonk noted another researcher’s definition of the kind of stress we are dealing with:

“the interaction between three elements: Perceived demand, perceived ability to cope, and the perception of the importance of being able to cope with the demand.”

Not Just PT

Vonk’s work indicates there is a significant difference between elevated HR from physical exertion versus an increase due to physiological and psychological stressors.

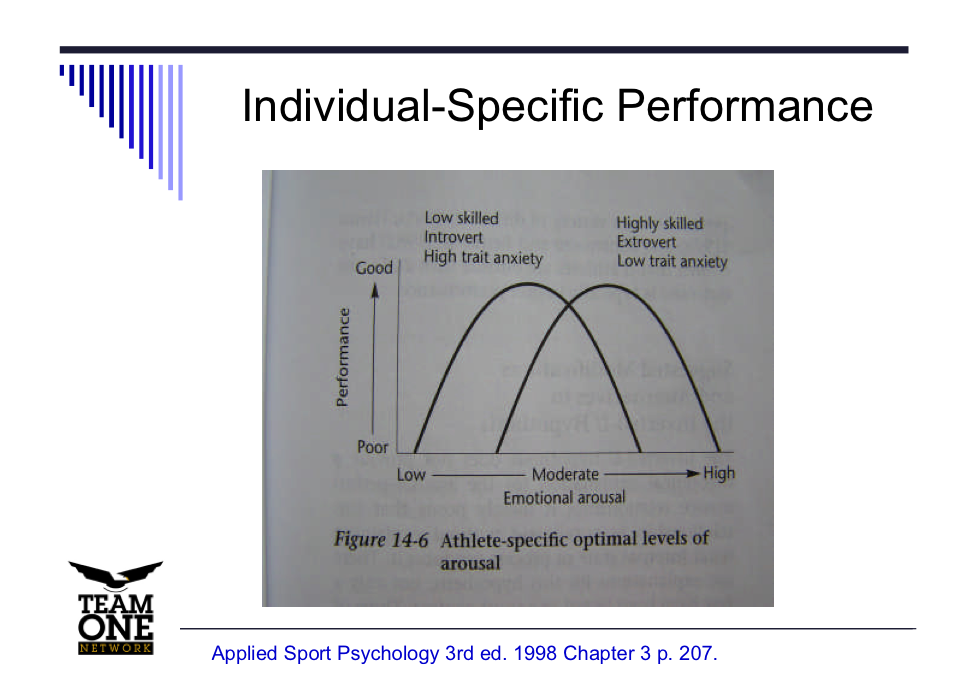

Focus on specific numbers may be misleading. Optimal performance is very individualized in nature. Vonk coined a phrase, the Individualized Zone of Optimized Functioning (IZOF).

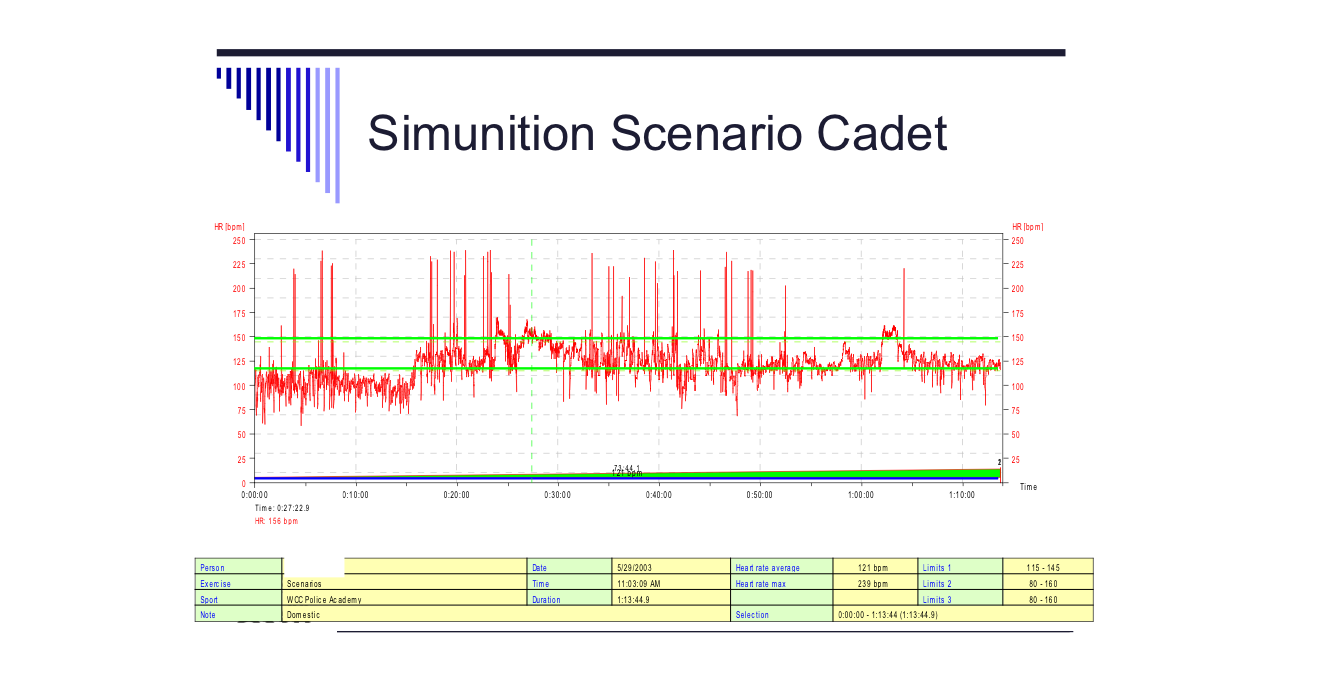

Six years of collecting HR data preceded this work. She had used heart rate monitors on both academy recruits and officers attending in-service training. Those with the monitors had been involved in physical fitness, use of force, vehicle operations, and reality-based training (RBT). She was also able to have on-duty officers wear those monitors while responding to calls for service, ones that involved physical exertion and those that did not.

As mentioned, she found there is an individualized component to this. Using blanket numbers for everyone is not the best practice.

Task Complexity

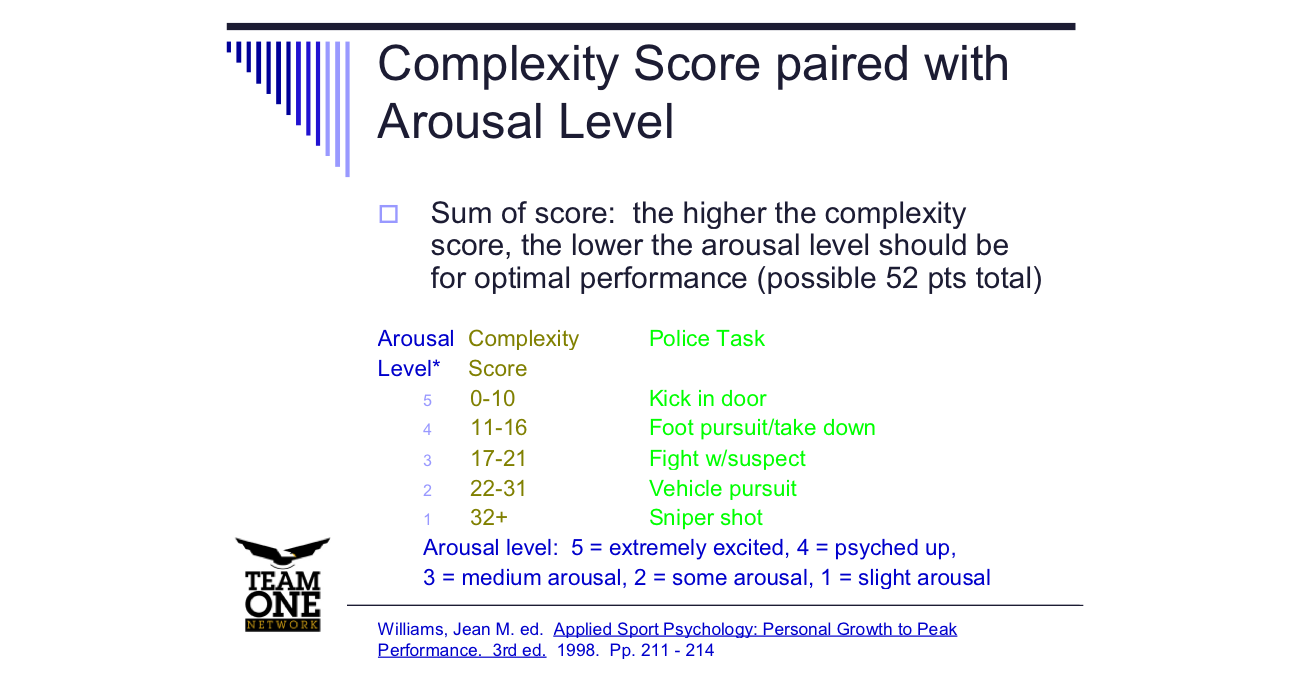

Every task can be evaluated in terms of complexity. The higher the complexity, the lower one’s level of arousal should be for optimal performance. A very complex task coupled with high levels of anxiety about the event and one’s skills would be a recipe for poor (or worse) performance.

Vonk noted the effect of several other issues while recommending IZOF. These included one’s personality characteristics, maturity level, levels of anxiety, coping skills, task complexity, and skill complexity. Personal development, physical skill improvement, maturity, and practical experience impacted these.

Heart rates from reality-based training will be different from those from PT sessions (PC ksat.com).

If physical exertion was not a factor, a lower HR did equate to better performance. And while a higher HR curve correlated to worse performance, it did not mean a bad or catastrophic outcome. If there were more frequent spikes in an officer’s HR spikes, then their performance would be worse.

She also noted that one’s experience had a relationship with more proficient performance and lower HR. That observation is consistent in several of the more recent studies.

Because Vonk’s work is over fifteen years old now, it seems some may have forgotten or overlooked it.

Daily Applications

Of note, in Vonk’s paper, she writes: “Monitoring heart rate is one of many methods to keep track of and control stress levels for some people, but it is still a valuable tool for police and military trainers who strive for current and future performance-improving applications.”

Heart rates for on-duty officers were also tracked on calls where they physically exerted themselves.

Recently, I gave a presentation covering some of the research on heart rates and stress by Vonk and others at the RangeMaster Tactical Conference. One attendee is a currently serving Army officer from the US Army’s Special Warfare Center and School. In a conversation afterward, he said the school has been using HR monitors on the students throughout the courses there. That performance data performance is collected and used in all phases of the training there.

Vonk was definitely a forward thinker.

Final Thought

In the last few years, articles and papers have appeared from the Force Science Research Center, among others. I’ll cover some of those in a future article. Better information in this area would benefit all our students, regardless of title.