box-eitjer2022-09-26 at 7.45.47 PM

“Life is like a box of chocolate; you never know what you’ll get until you bite into one.”

Whether pro-active policing is still a thing or not, working street cops will make traffic stops. Most of the time, the officer has no idea who is in the vehicle and what they were doing – like biting into that box of chocolates.

Vehicle stops are the most common interaction between police officers and the public. When I write ‘police officer,’ I am also referring to deputy sheriffs, state troopers, highway patrol officers, and those with similar jobs.

In 2017, the U.S. Department of Justice released a study of law enforcement fatalities. The authors wrote in “Making it safer: A study of law enforcement fatalities between 2010-2016” that more than half of the officers killed during self-initiated events were killed during traffic stops.

For cops making traffic stops, the goal should be to do it as safely as possible for all involved. Part of making it safe for all involved is to handle the stop so that you can focus your attention on those in the vehicle and their actions and behaviors. How can you best do that?

After the vehicle has been stopped, you can contact the driver in three ways. You can:

- Approach on the driver’s side.

- Approach on the passenger side.

- Call the driver back to you.

Calling the driver back separates the driver from the vehicle and anyone else in it. However, are other people in the car, truck, or SUV? Now your attention is divided between the two. And you may not know what and who is in the vehicle for quite a while.

Approaching from the driver’s side is common; however, it can create some other issues. Now, the officer is in or very near the roadway. Along with being concerned about the driver and passengers, the officer must also worry about passing traffic.

The California Highway Patrol is a strong advocate for passenger-side approaches – and they do a lot of driving under the influence investigations.

When I asked why officers made driver’s side approaches, I received several answers. The three most common ones were: that is how I was taught to make them; the terrain, geography in my area/beat (cliffs, guard rails, etc.) doesn’t allow for passenger side approaches; and I can better identify drunk drivers.

What about passenger-side approaches? Well, they keep the officer out of the roadway. Are there any other benefits?

Multiple studies indicate that an officer on the driver’s side has a greater chance of not seeing critical actions, behaviors, or objects inside the passenger compartment.

Also, there seems to be a greater chance of an officer on the driver’s side trying to physically stop a driver from fleeing by reaching into the car or grabbing onto the driver and getting drug by the vehicle.

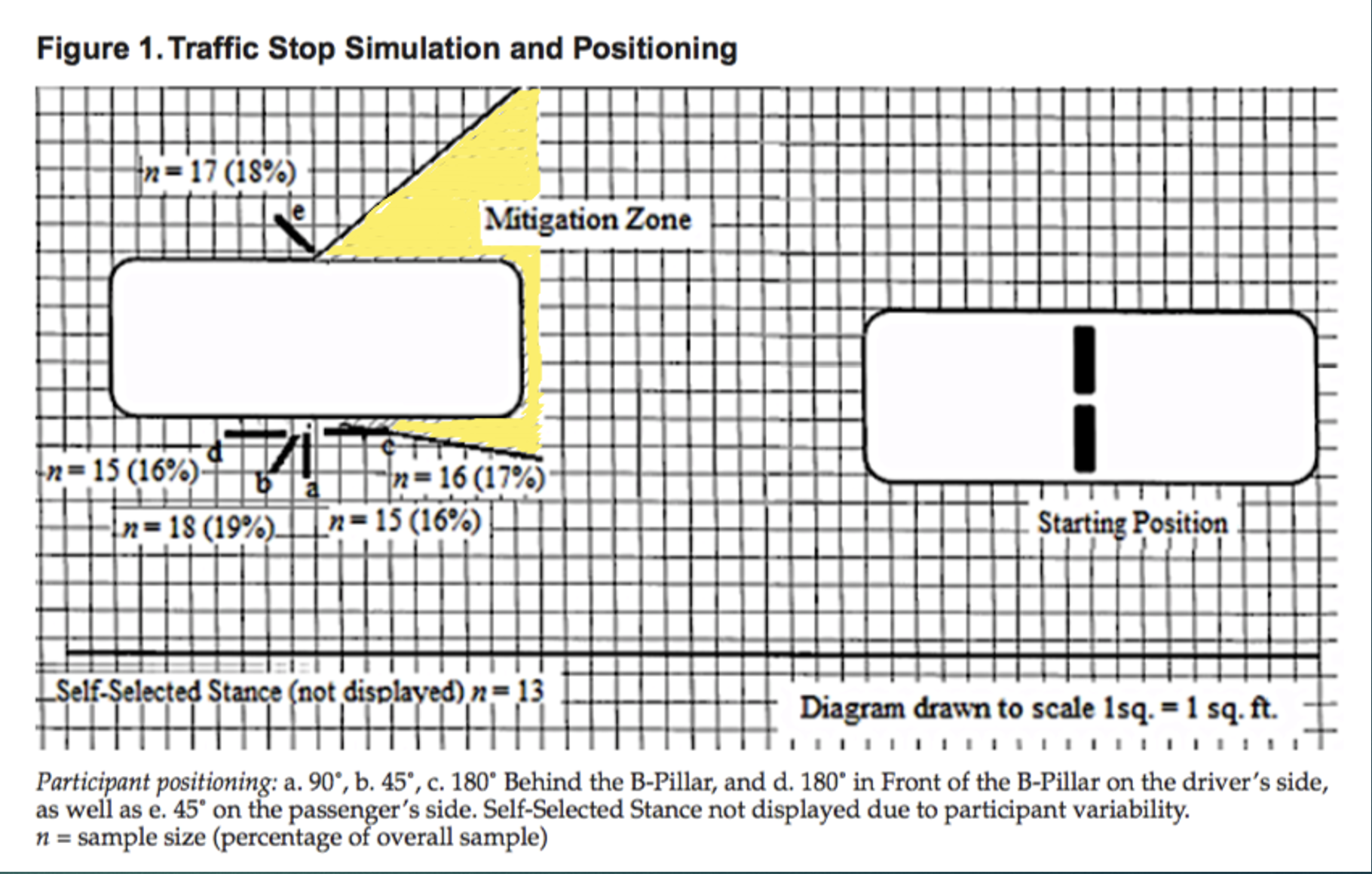

Force Science’s study on positioning during vehicle stops identified a safe zone for officers. They got to it sooner on the passenger side.

Finally, there is an increased likelihood of the officer getting to research defined “safe” place sooner when working on the passenger side. That information comes from a study done by Force Science in conjunction with the Hillsborough, Oregon Police Department, and surrounding agencies. Three key findings from that effort:

- When on the passenger side, an officer can get to a position of safety in 0.56 seconds faster than an officer on the driver’s side, which was by moving only a couple of feet.

- Moving to that safe zone and then drawing was faster than trying to move and draw simultaneously.

- Most common driver’s side approaches “fail to adequately protect officers against the threat of lethal force.”

The 2017 DOJ study previously mentioned said, “A right-side approach is the safest to protect against struck-by crashes and may tactically put the driver at a disadvantage as the approaching officer has some limited protection afforded by the vehicle’s door frames.”

Over half of the recruits and one-third of the working officers in this study missed the gun on the dashboard.

A police academy in the U.S. midwest did another study in 2017. It looked at driver’s side approaches and inattentional blindness on the part of both recruits and officers attending in-service training. The scenario involved a handgun placed to the driver’s right on the dashboard. Out of one hundred recruits, fifty-eight did not see the handgun. Seventy-five in-service officers participated, and twenty-five of them (one-third) also missed the handgun.

If an officer has a reduced view of the interior in the passenger compartment, can the officer see more from the passenger side?

Law Officer magazine had an article discussing a 1999 study from a large California agency that looked at driver’s and passenger side approaches on a car with an “armed” subject hiding in the back seat. 90% of those making a driver’s side approach missed seeing the suspect, while only 10% of those on the passenger side failed to see him.

During this 2013 traffic stop, the Westerville, Ohio Police officer made a passenger side approach and saw a handgun in the driver’s lap (from the Westerville PD dash cam).

Another example is the 2013 traffic stop and subsequent officer-involved shooting by a Westerville, Ohio, officer. Approaching on the passenger side, he saw the driver leaning out the driver’s window. The driver was also holding a handgun in his lap. Even though there was a passenger in the car, the officer could see the driver and the handgun. When commands proved unsuccessful, the officer was able to prevail in the subsequent shooting.

If you are going to open and bite into the proverbial box of chocolates, it makes sense to do it from a safer position with better visibility.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)