Screenshot 2023-11-07 at 7.25.54 AM

I was comparing notes on new products with American Cop Editor Erick Gelhaus at the 2023 SHOT Show, and the conversation turned towards law enforcement duty holsters. Each of us had seen some promising leads, and we were eager to share what we had learned with each other.

Alas, the conversation highlighted one of my pet peeves in the holster industry, which is the lack of standardization in the terms we use to describe security and retention features. As I explained a new entry into the duty holster market, I had to warn Erick that although the manufacturer had declared it to be a “Level III” security holster, I thought it was really a “Level I,” instead. That led us into a sidebar conversation, which we soon realized we should probably share with the American Cop audience.

The Holster of Babel

The honest truth is that there’s so much confusion about the retention “levels” assigned to holsters, that the terminology has become rather meaningless, over time.

There’s no equivalent to the National Institute of Justice’s (NIJ’s) Body Armor Performance Standards when it comes to retention holsters, and no centralized agency like NIJ to test and certify duty holsters for their retention qualities.

Every manufacturer has their own interpretation of what the retention “levels” are, and how a holster should be rated, so while they often use the same terminology, they’re frequently talking about very different things. When you compare a “Level III” holster from Brand X, to a “Level III” holster from Brand Y, there’s absolutely no guarantee that the two products will have similar retention qualities–same term, different meanings.

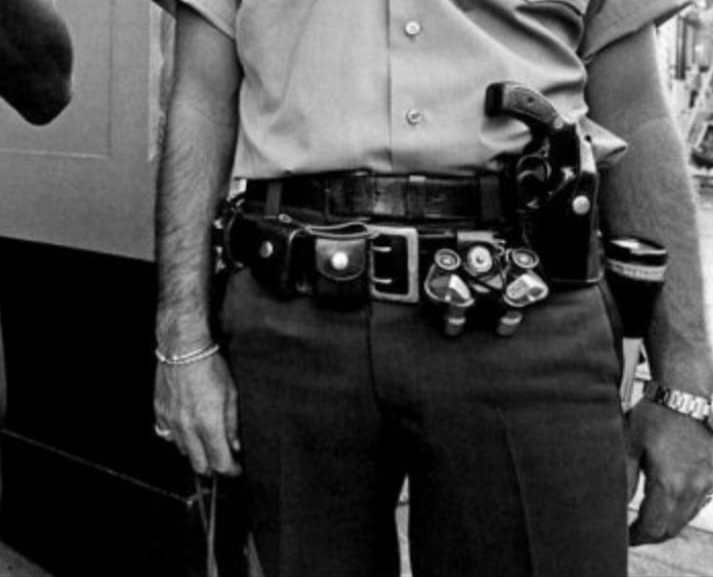

The Bianchi Judge, a break-front holster – this was still a common design in the late 80s (Courtesy: R Garret).

The sad truth is that a holster’s retention “level” has as much to do with marketing as it does with the product’s features, and officer safety. I wish that wasn’t true, but it is, and you need to understand it as a person who purchases, issues, or uses this equipment.

Origins

To understand how we got here, we need to go back to where we started.

The concept of holster “retention levels” originated with the Rogers Holster Company, in the early 1970s. Former FBI Special Agent, and company founder, Bill Rogers, created a testing protocol around 1975 to award retention “levels” to the security holsters he was building for law enforcement duty use.

First Test

In Rogers’ test, an officer would don his duty belt with his holstered firearm, ensuring that all the security devices were properly engaged (straps in place, snaps closed, and so forth). Then an “attacker” would grab the holstered firearm by the grip, and attempt to remove it from the holster by pulling and twisting on the grip for a period of five seconds. The attacker would not try to disengage the holster’s security devices (i.e., unsnap a snap, or remove a strap), but would just try to pull the gun out of the holster to the front, to the rear, straight up, and away from the officer’s body. The officer would not take any action to stop the simulated gun grab–the holster did all the work of retaining the gun in the test.

If the gun stayed in the holster for five seconds, and the holster stayed attached to the officer, then it was deemed a “Level I” holster in Rogers’ system, and a second test would be accomplished.

Second Test

In the second test, the officer would take the first action required to disengage the holster’s primary retention or security device, in preparation for a draw, and leave it in that condition for the attacker. In example, if the holster had a simple, snapped retention strap to keep the gun in place, then the officer would pop the snap on the retention strap (but would not move the strap out of place) in preparation for the second test.

If the holster passed another five-second test in this condition, then it was rated as a “Level II” holster. If it did not retain the gun, then it remained a “Level I” holster, only.

At some point, the fight over a holstered pistol can require a deadly force solution. And the “when” can vary.

Additional five-second tests would be conducted as warranted, based on the holster’s security features, with each feature being disabled in the same sequence that would be required for a draw. At the time the test protocol was created by Rogers, there was only one holster in production (Rogers’ SS3) that qualified as a “Level III” holster, based on its ability to withstand three different five-second attacks, as the holster’s security features were disabled, one-by-one.

Next Time

The second part of this article will address what happened with Rogers’ holsters, changes in the industry because of other companies, the need to test and verify, and the state of duty holster design.

About the Author:

Mike Wood is a law enforcement trainer and an instructor with National Training Concepts. He’s the author of Newhall Shooting: A Tactical Analysis, the acclaimed study of the 1970 gunfight that shaped police training, equipment, and culture for generations. Mike also serves as the Senior Editor at RevolverGuy.com.