med_cover

Having the equipment you might need is more important than how you carry it.

Which are you more likely to use: Medical skills? Defensive firearms skills? Before we look at the numbers, I’ll say that on the day you need either one, that skill set will be the most critical thing you must perform.

Data:

In thinking about the likelihood of needing specific skills, I looked at the number of vehicle accidents with injuries compared to the number of aggravated assaults. I went with the numbers for both from 2019. Why? It was not only the last non-Covid year, but we had not seen the widespread urban and suburban rioting coupled with the defunding of the police movement. There were 1,916,344 non-fatal injury accidents. In contrast, there were 821,182 aggravated assaults – not homicides,

Back then, the population of the United States (total residents) was 328,239,523. 2,737,526 were injured in a car wreck or were victimized by a felony assault. This does not include plain old, everyday accidents or other, more serious assaults.

So, while I have some old pre-hospital medical experience, I am not a subject matter expert. I reached out to former U.S. Army medic Caleb Causey of Lone Star Medics. While serving, he deployed overseas and worked with at least two different operational airborne organizations. Domestically, he has done considerable work in the pre-hospital care environment. And he taught the last non-institutional medical training I’ve taken.

I asked Caleb about his thoughts on training, personal gear, and vehicle-based equipment. He gave me the fire hose answer that included the bare minimum, realistic, and most desirable outcomes. A couple of them even surprised me.

We did not specifically talk about airway management. If you are trained to use them, why not carry them? Just remember to bring the lube.

Training:

The absolute bare minimum training he thinks law enforcement should have is a Stop the Bleed class. At least, they will walk away knowing how to apply a tourniquet, use a pressure dressing to a wound, and pack a wound with gauze.

While he was not positive about the year and the exact number, the last time he checked the data, traffic accidents caused more injuries to officers than anything else. The profession see-saws on whether it is gunshots or car wrecks that kill more of us. In that data, he also saw that head and neck injuries were the most common killers, followed by wounds to the abdomen, then the extremities. Thoracic injuries were the fewest, generally because of body armor. Some neck injuries can be survived IF you can pack those wounds. That requires both skill and the right equipment.

We also talked about higher levels of training. Tactical Combat Casualty Care and its civilian equivalent Tactical Emergency Casualty Care are worthwhile classes. The concern is the context and applicability. However, officers are more likely to do self or buddy-aid instead of being in a mass casualty event.

Traditional programs like First Responder, EMT-Basic, and EMT-Wilderness can be too broad. Most officers don’t need to know how to work in an ambulance-based pre-hospital, 9-1-1 system. How many patrol cars have O2 tanks in them?

Caleb noted an exception would be a public safety-like department where the officers are responding with the firefighters – giving the Dallas-Ft Worth Airport police as an example. He added that EMT-Basic may be a solid foundation for additional levels of training.

In discussing training, we talked about testing. Caleb believes, and most of us would agree, that officers must have their training and skills pressure tested. However, that testing needs to be grounded. Full-blown scenarios are nice, but not at the expense of training time in shorter classes. Moulage & “rocket propelled grenade simulators” (which he has really used) aren’t needed until the students have the skills and can perform them – like at the end of a two-day class. We aren’t running force on force at the start of an entry-level pistol class.

Recertification or recurrent training, at a minimum, should be 4-hours every year. If the supervisors are having the cops work drills regularly in a briefing, then 1-2 hours every six months would be ideal.

Caleb gave an example of why update training is essential for all practitioners. Like I’d been told, he taught that the tourniquet needed to be applied “High & Tight” – as high up on the affected limb as possible. While talking with a peer, he learned the new standard was 2” to 3” inches above the wound.

If we qualify with our guns yearly, we should be training on our medical skills yearly as well.

Equipment:

On you for self or buddy aid.

Per Causey, the bare minimum on you, in uniform, is a Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care (COTCCCC) approved tourniquet (TQ), two vented chest seals, wound packing material, and an EDC pressure bandage.

COTCCC are the providers who certify the techniques and equipment used in trauma medicine. Neither the RATS nor the SWAT-T tourniquets are approved by that committee. Wound packing gauze comes from H&H Medical Corporation or Quik Clot combat gauze impregnated with an anti-bleeding agent. H&H, 1110, and Persys Med all make good pressure bandages.

My ankle med kit from The Wilderness – gloves, another TQ, QuikClot gauze, trauma bandage, and chest seals.

We both like ankle cuffs to carry our med gear. I use The Wilderness’ offering, while he prefers the FrogPro from Safer Faster Defense.

In Your Vehicle:

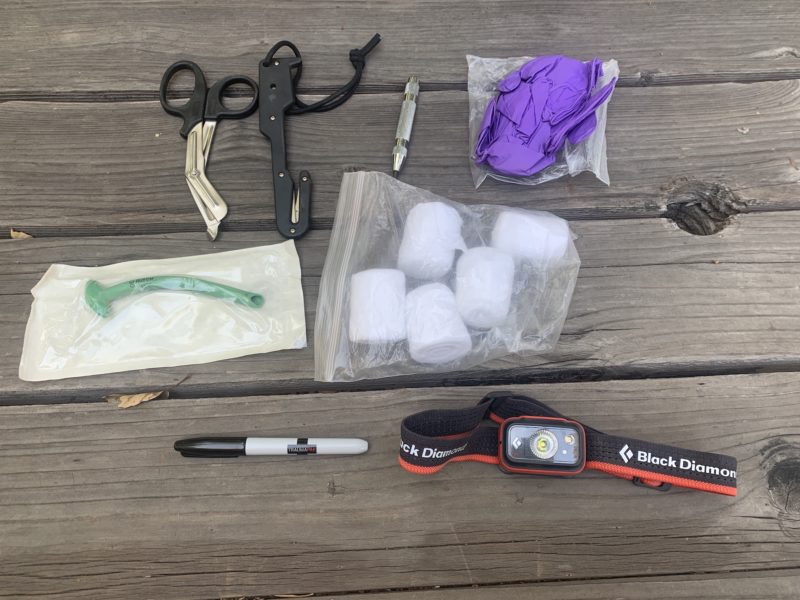

This kit stays in my truck. Extra TQs, dressings, gauze, airways, and a headlamp – how well can you hold a flashlight and work on a patient?

COTCCCC approved TQs (2-4); Full-size Olaes battle dressings (named after a Soldier killed in AFG) (2-4); 4-yard-long wound packing gauze with hemostatic agents (4-6); 8-12 chest seals in the bag, both vented & HALO for impaled objects which can be cut to fit (8-12); Gloves; Triangle bandages (2-12); Headlamp; Sharpies; Shears or Benchmade rescue hooks; Large abdominal-size dressing (1); SAM splint (optional); and Space or Blizzard Blankets (double layered space blanket).

Caleb cautioned against keeping a visible headrest kit in your vehicle because of auto burglaries.

As cops and citizens, our role is to control hemorrhaging (Stop The Bleeding) through bandages, wound packing, and chest seals or tourniquets. We all need the training and equipment to do that.

Resources:

https://jts.health.mil/index.cfm/committees/cotccc

saferfasterdefense.com/product/sfd-responder/

tacmedsolutions.com/products/sof-tourniquet

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)