2000

To shoot or not to shoot is the decades-old question when confronted with the decision to shoot the driver of a vehicle you perceive as intending to run you over. Some departments strictly forbid their officers from shooting at moving vehicles.

As with any use of force, there are many factors to consider. One thing an officer usually does not have – in the middle of “… a tense, uncertain, rapidly evolving event” – is time.

What can you consider now, before you are placed in a position to consider shooting into a vehicle?

Can you get out of the vehicle’s way? Are there physical barriers between you and the vehicle? If the vehicle is moving, what direction is it traveling, and is that a threat to you? As it travels towards its intended target, you, or others, are there bystanders behind the vehicle? Are you able to disable the vehicle, not the driver? The position of the officer at the time of the shooting would be telling if the officer intentionally placed themselves in the path of the vehicle.

One of the cardinal safety rules; know your target and what is beyond it. How does that affect your ability to engage the vehicle’s occupants?

Supreme Court rulings regarding shooting into vehicles have been inconsistent. Several circuit courts have followed suit. The differences have included the officer’s position in relation to the vehicle’s path as well as the suspect’s behavior and level of violence.

How do the courts view officer-created jeopardy regarding officers shooting into vehicles? Consider the appellate court ruling in Quezada v. County of Bernalillo 944 F.2d 710 (1991) from the Tenth Circuit. In addition to several other claims, the court found a deputy acted negligently when he moved to a very close distance (five feet) from the door of the suspect’s vehicle and subsequently fatally shot her.

Most drivers will be concealed behind the engine, firewall, and dash, significantly reducing the available target area, never mind the vehicle’s movement. Many of us know members of our departments that have difficulty hitting a static target while stationary. Now add in a moving target, reduced target area, and getting out of the vehicle’s way. A headshot on a static target is difficult; a headshot on a moving target behind a windshield is even more difficult.

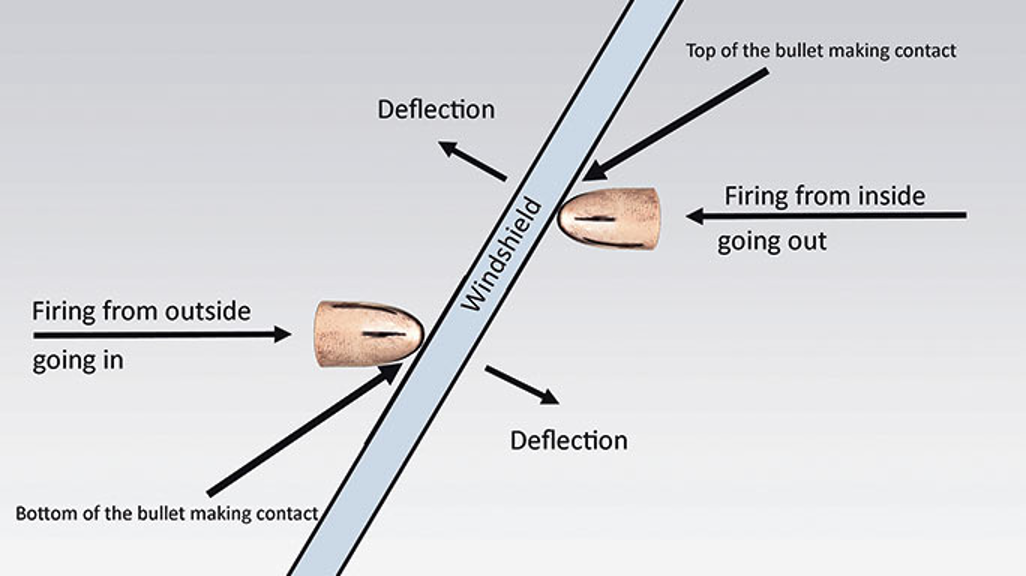

How bullets deflect when going through a windshield, going out, or going in. (Photo used with the permission of Fred Mastison, ForceOptions USA)

How many officers have witnessed the effect windshield glass has on a bullet? A bullet fired into the windshield from outside the car will deflect downward. This has to do with the amount and location of the bullet’s contact with the windshield. After the bullet hits the windshield, there is less contact below the projectile than above. That causes the bullet to go low. It is generally the opposite for a bullet going out of the windshield. If the shooter’s point of aim is at the head of the driver, it is likely the bullet will travel downward, striking the dash, steering wheel, or a smaller area of the driver. If the bullet does strike the driver, it could incapacitate them, creating an uncontrolled weapon.

What are the immediate priorities when facing a vehicle attempting to run you over? Do you get out of the way or square off and shoot the driver? One law enforcement agency policy says, “Except, in rare circumstances, the danger permitting the officer to use deadly force must be by means other than the vehicle.” The driver driving the vehicle toward an officer fails to reach the level of deadly force authorized.

How much is that projectile going to deflect when it goes through the windshield? Or any other part of the vehicle?

Due to the vast amount of variables, any decision to shoot into a moving vehicle with the sole purpose of incapacitating the driver is, at best, difficult. And that is if you hit the driver – not any passengers, bystanders, or the vehicle. If the vehicle turns away or you can move out of the way, you may shoot into the side or rear of a vehicle that no longer poses an imminent threat to you. The choices are – to get out of the way or create an uncontrolled weapon.

Making the decision to shoot at a moving vehicle can be as difficult as seeing out of the windshield.

West Jordan, Utah Chief Ken Wallentine has written, “No one can dispute physics: 12 grams of lead and copper will nearly always be trumped by 3,000 pounds of steel, rubber, and plastic. … Nonetheless, the Supreme Court has considered and rejected a bright-line holding that firing into a vehicle is objectively unreasonable in all circumstances.”

The case of Estate of Christopher J. Davis v. Ortiz, 2021 WL 402487 (7th Cir. 2021) is based on the events stemming from a buy-bust operation involving a confidential informant. While attempting to stop the fleeing suspect, Deputy Ortiz fired four bullets into the suspect’s vehicle while the vehicle was coming toward him from fifty feet away. Deputy Ortiz testified he was attempting to stop the vehicle instead of shooting the vehicle’s occupants. One of those bullets struck a passenger, Davis, in the head. The court denied Ortiz qualified immunity. How an officer articulates the events leading to the determination to shoot into a moving vehicle profoundly impacts whether the court views the event as objectively reasonable.

In Plumhoff v. Rickard, 572 U.S. 765 (2014), the Supreme Court held it reasonable for an officer to shoot into a moving vehicle to end a pursuit. The pursuit was lengthy, and Rickard continued to attempt to flee after being blocked in by police in a cul-de-sac. The officers reasonably believed that if Rickard could flee, he would pose a deadly threat to others if the pursuit continued. Rickard and his passenger Kelly Allen were killed in the shooting. The Supreme Court ruled the officers did not fire more shots than were necessary to end the risk to public safety. The ruling addressed a claim of excessive force filed by the driver’s family, not anything about the passenger or the suspect’s presence in a vehicle.

There are a number of considerations that go into your decision to shoot at a moving vehicle.

West Jordan, Utah Chief Ken Wallentine has written, “No one can dispute physics: 12 grams of lead and copper will nearly always be trumped by 3,000 pounds of steel, rubber, and plastic. … Nonetheless, the Supreme Court has considered and rejected a bright-line holding that firing into a vehicle is objectively unreasonable in all circumstances.”

Making the decision to shoot at a moving vehicle can be as difficult as seeing out of this windshield.

The case of Estate of Christopher J. Davis v. Ortiz, 2021 WL 402487 (7th Cir. 2021) is based on the events stemming from a buy-bust operation involving a confidential informant. While attempting to stop the fleeing suspect, Deputy Ortiz fired four bullets into the suspect’s vehicle while the vehicle was coming toward him from fifty feet away. Deputy Ortiz testified he was attempting to stop the vehicle instead of shooting the vehicle’s occupants. One of those bullets struck a passenger, Davis, in the head. The court denied Ortiz qualified immunity. How an officer articulates the events leading to the determination to shoot into a moving vehicle profoundly impacts whether the court views the event as objectively reasonable.

In Plumhoff v. Rickard, 572 U.S. 765 (2014), the Supreme Court held it reasonable for an officer to shoot into a moving vehicle to end a pursuit. The pursuit was lengthy, and Rickard continued to attempt to flee after being blocked in by police in a cul-de-sac. The officers reasonably believed that if Rickard could flee, he would pose a deadly threat to others if the pursuit continued. Rickard and his passenger Kelly Allen were killed in the shooting. The Supreme Court ruled the officers did not fire more shots than were necessary to end the risk to public safety. The ruling addressed a claim of excessive force filed by the driver’s family, not anything about the passenger or the suspect’s presence in a vehicle.

There are a number of considerations that go into your decision to shoot at a moving vehicle. This is not a decision to make lightly.